We’ve traced the Baptist story in England throughout the 17th century. Now, we turn our attention across the Atlantic to what was happening among Baptists in America during the same period. My aim is to carry us through both the 17th and 18th centuries of American Baptist history.

From English Roots to American Soil

When we think about the early religious history of America, many of us picture the Pilgrims. We learned about them in school. They were English Separatists who migrated in the 1620s in search of religious freedom. We may even imagine the familiar scene of a shared meal with Native Americans already living here. It’s an appealing picture of liberty and peace. In reality, however, religion in early America was far more complicated, and for Baptists, far harsher.

Any hope of broad religious freedom quickly faded as the Pilgrims were followed by as many as 20,000 Puritans over the next two decades, most of whom settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

These Puritans were not Separatists. They held Reformed, Calvinistic convictions, but they did not believe in leaving the Church of England altogether. Instead, they sought further reform within it and remained loyal to it. At the same time, they practiced a congregational form of church government, which set them apart ecclesiologically from Anglicanism.

This creates one of the first ironies in the American Baptist story. In England, Congregationalists were Separatists. Men like John Owen left the Church of England. In America, however, Puritan Congregationalists remained loyal to the Church of England, even as that same church persecuted Congregationalists back home.

The irony deepens. These Puritans came to the New World, at least in part, to practice congregationalism and enjoy a measure of religious liberty. Yet they remained aligned with the Church of England and soon became the primary persecutors of Separatists and Nonconformists in America, including Baptists.

To understand this, we have to remember that they were attempting to build an entirely new society. When early Baptists in England argued for complete religious freedom, those ideas were largely theoretical. No one had yet attempted to implement them on a societal scale. The prevailing assumption was that unrestricted religious liberty would lead to social collapse and chaos. As a result, the American Congregationalists believed the society they were constructing had to be uniform. Nonconformity, in their view, threatened the very foundations of social order.

That does not excuse their persecution, but it does help explain it.

The irony becomes even sharper when we consider how much the Congregationalists and Baptists shared. Both were orthodox and evangelical. Both practiced congregational polity. Early American Baptists also shared Calvinist convictions. While that would change over time, most American Baptists in the 17th and 18th centuries were Calvinists.

Still, two differences loomed large—differences the Congregationalists believed were dangerous enough to undermine society itself—that is, believer’s baptism and the separation of church and state.

Roger Williams and the Birth of American Baptist Life

With that context in mind, the Baptist story in America begins with the arrival of Roger Williams in 1631.

Williams was a gifted and well-educated figure, a Cambridge-trained Puritan minister in his early thirties. He possessed an intimate knowledge of English politics, having previously developed a shorthand system that allowed him to record parliamentary debates word for word in real time. He was invited to document parliamentary sessions, which gave him unique insight into the relationship between church and state. That background may help explain why he became such a strong advocate for their separation.

When Williams arrived in Boston in 1631, he was invited almost immediately to become a teacher at the church. It was a prestigious offer. Boston was the center of power in Puritan-controlled Massachusetts, yet Williams declined. His reason was simple and provocative: the church in Boston was not sufficiently separated from the Church of England. He called them an “unseparated people,” arguing that they still retained too many Roman Catholic superstitions and maintained ties to the English church that were too strong.

From there, Williams moved from Boston to Salem, then to Plymouth, and back again to Salem. Everywhere he went, he pressed ideas that made people uncomfortable. For his time and place, Williams was a radical. By 1635, the Massachusetts General Court had had enough and brought formal charges against him.

The controversy centered first on Williams’s attack on the colony’s legitimacy. The Massachusetts Bay Colony existed under a royal charter that granted the English the right to take land from Native Americans. That charter assumed the superiority of Christian nations over non-Christian peoples and claimed divine authority for England to seize indigenous land. Williams rejected this outright. He argued that the charter was both illegal and immoral. For the 1630s, this was extraordinarily radical thinking.

Several charges were brought against him, but the most serious concerned his rejection of forced religion. Williams denied that civil magistrates had authority over what he called “soul” matters. Like the English Baptists, such as John Murton writing from prison, Williams believed the government should enforce the second table of the Ten Commandments, but not the first. His reasoning was straightforward. The “sword of steel,” the coercive power of the state, cannot change the human heart, and true Christianity requires a changed heart. Scripture, he argued, gives no authority for the church to wield the sword of steel at all. The church’s weapon is the sword of the Spirit. He laid out this case in The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution, arguing from history and, above all, from Scripture that the government has no right to compel religious belief.

In 1635, the verdict came down. Williams was convicted of spreading “diverse new and dangerous opinions,” and plans were made to send him back to England for imprisonment. Before that could happen, Williams fled. He kissed his wife and two young children goodbye and escaped into the wilderness.

It was January 1636. A New England winter had set in with deep snow, bitter cold, and weeks of subfreezing temperatures. For fourteen weeks, Williams wandered in the wilderness. He later wrote that he “knew not what bread or bed did mean” during that time. He likely would not have survived had it not been for the relationships he had cultivated with local Native Americans. He had defended their claim to the land and learned their language. In one of the sharpest ironies, they showed him greater charity than his fellow Christians in Boston, taking him in and sustaining him through the winter.

When spring arrived, Williams purchased land from these Native Americans to establish a settlement. He insisted on paying for it and named the settlement Providence, believing God had preserved him through his suffering.

The rules of this new settlement in Rhode Island were simple. Regardless of religious belief—Puritan, Quaker, Jew, Catholic, atheist—everyone enjoyed full religious liberty, provided they obeyed civil laws. Matters of the soul were left to the individual. This marked the first place in modern history where citizenship was not tied to adherence to a particular church or religion.

Providence soon attracted a wide range of Nonconformists, and it was here that the first Baptist church in America emerged. Around 1638, Williams became convinced that only believers should be baptized. True Christianity, he argued, requires faith and a changed heart—something an infant cannot possess. Infant baptism, therefore, was not an expression of faith but an act imposed by force. Baptism, Williams concluded, must be voluntary and reserved for believers. He baptized Ezekiel Holliman, who then baptized Williams, and together they baptized roughly twelve others. With that, the first Baptist church in America was formed.

Yet, much like John Smyth, Williams did not remain with the church for long. Within three or four months, he became convinced that his baptism was likely invalid. He went further than Smyth, though, concluding that the church itself had been illegitimate since at least the fourth century. He traced the problem to the reign of Constantine, when church and state were joined together. Williams viewed that union as apostasy and the corruption of the true church.

This raised a serious question. If true church authority depends on legitimate succession, and the church had been corrupt for centuries, how could a true church be restored? Williams’s answer was that only God could do it. New apostles would have to be sent with apostolic authority. At this point, Williams became what was known as a Seeker. He left the Baptist church and, though he retained Baptist convictions, chose to worship privately while waiting for God to send new apostles and restore the true church.

John Clarke and the Rhode Island Charter

At the same time, another figure emerges in Rhode Island, often overshadowed by Roger Williams, who proves even more significant for the Baptist cause: Dr. John Clarke. Clarke was both a physician and a theologian, and he founded the second Baptist church in America in Newport, Rhode Island. Some argue this should be considered the first Baptist church because it was the first to practice baptism by immersion. The Providence church would soon follow, and immersion would become the universal practice among Baptist churches thereafter.

By the 1640s, Clarke had become something of a statesman. He was deeply committed to liberty of conscience and spent roughly twelve years traveling between Rhode Island and England. During the turmoil of the English Civil War, he worked tirelessly to secure a legal charter for Rhode Island before Massachusetts could absorb the colony and impose its state religion.

In 1663, Clarke succeeded. The achievement was remarkable for at least two reasons. First, the charter explicitly guaranteed religious liberty for all. It declared that no person could be “molested, punished, disquieted, or called in question” for matters of religious belief. Clarke sought what he called “permissive freedom in respect of the worship of God,” in contrast to forced worship, which he argued was not worship at all.

Second, the charter was granted by King Charles II, the same monarch who was actively persecuting Baptists in England. Yet here he was, at the request of a Baptist minister, extending legal protection to all religions in Rhode Island.

Why Charles II agreed to this remains a matter of speculation. Some have suggested he was a Catholic sympathizer and viewed Rhode Island as a potential refuge for Catholics. Whatever his motives, God was once again drawing a straight line with crooked sticks.

To appreciate the significance of this charter, we need to step back a few years and consider the severity of Baptist persecution in New England. The charter was not merely symbolic. It was hard-won and momentous, not only for Baptists, but for the future of religious liberty in America.

Obadiah Holmes and the Cost of Religious Liberty

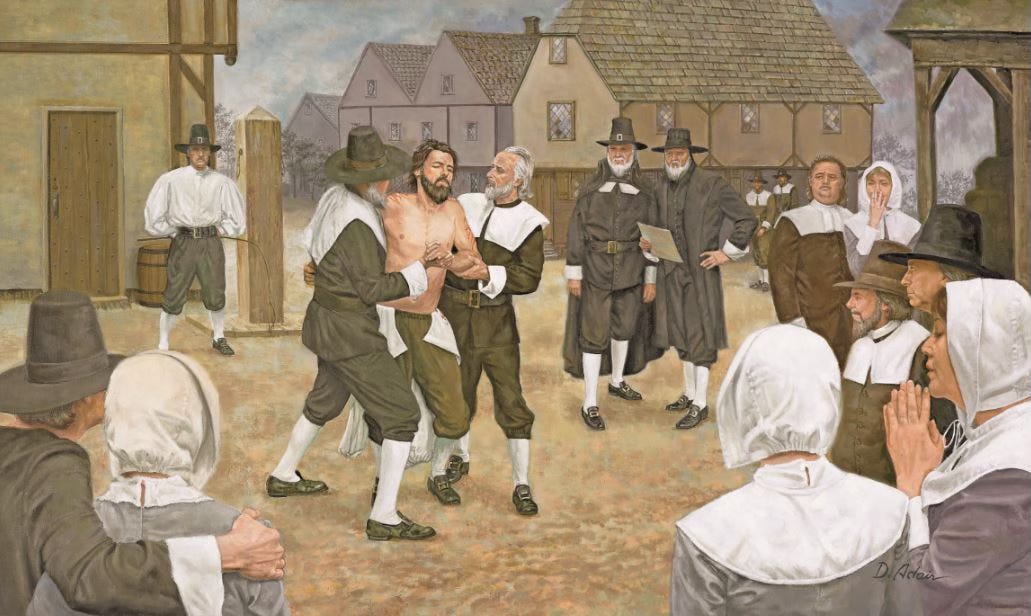

Baptists did not grow as quickly in America as they did in England, but individuals with Baptist convictions were scattered throughout New England, including Massachusetts Bay. In 1651, a blind, elderly Baptist living in Massachusetts was unable to travel to Clarke’s church in Newport. Clarke, along with John Crandall and Obadiah Holmes, walked nearly eighty miles to visit him, share the Lord’s Supper, and worship privately in his home. While they were meeting, authorities burst in and arrested them.

Rather than taking them directly to jail, the magistrates forced the three men to sit through a Congregationalist worship service. That might have been the end of the matter, but in protest against forced religion, they refused to remove their hats during the service. Afterward, they were subjected to what amounted to a mock trial. The judge accused Clarke, saying, “You go up and down and secretly drop your seed like a serpent.”

There was little pretense of justice. The magistrates viewed Clarke and his companions as no different from the radical Anabaptists of Europe. They were sentenced immediately and imprisoned until they paid heavy fines. Clarke was fined £30, roughly a year’s wages for a skilled tradesman. Crandall and Holmes were each fined £5. All three initially refused to pay, believing that payment would be an admission of guilt.

Clarke’s friends eventually paid his fine without his consent, securing his release. Crandall later chose to pay his own fine and was released. Obadiah Holmes, however, refused outright. He declared that whatever punishment the magistrates inflicted on him would stand as a testimony against the injustice of a state-controlled church.

On September 5, 1651, Holmes was taken to the public square in Boston. He was stripped to the waist, tied to a post, and whipped thirty times with a three-corded whip—ninety lashes across his back. It would be weeks before he could lie down to sleep, forcing him to rest on his knees and elbows. When they finally untied him, Holmes turned to the magistrates and said, “You have struck me as with roses.”

Later, he wrote to John Spilsbury, pastor of the first Particular Baptist church in England, describing how he experienced the “spiritual manifestation of God’s presence” to such a degree that the “outward pain was so removed.”

One might expect such brutality to crush the Baptist movement in America. Instead, it brought the debate over church and state out of the realm of theory and into the stark reality of human suffering. The Puritans appeared as persecutors, and the Baptists as martyrs. One witness later remarked that this whipping became the seed of the Baptist church. Coercion did not produce conformity; it exposed injustice.

Rather than extinguishing the movement, the whipping of Obadiah Holmes fueled its growth. Henry Dunster, the first president of Harvard College, was so affected by this event that he reconsidered infant baptism, a change that ultimately cost him his position. He was not alone. By 1665, despite determined opposition, a Baptist church had been established in Boston.

The Middle Colonies and an Unlikely Convert

From there, the Baptist story shifts south to the Middle Colonies, especially Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Pennsylvania, founded in the 1680s, was established on principles of religious freedom similar to those of Rhode Island. The first Baptist church there was planted by Thomas Dungan, a member of John Clarke’s church. Dungan lived only four years after planting the congregation, and the church itself did not survive much longer. Before his death, however, he baptized a man who would go on to evangelize widely and plant churches throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. His name was Elias Keach, and his story is one of the most striking in Baptist history.

Elias Keach was the son of Benjamin Keach, the well-known and highly influential Particular Baptist pastor in England. Yet at the age of nineteen, Elias was not a Christian. He regarded believers as naïve and easily deceived. Taking a cue from the prodigal son in Luke 15, he left home for the far country of Pennsylvania.

Before leaving, Elias stole some of his father’s sermon manuscripts and ministerial clothing. His plan was to expose what he believed was Christians’ gullibility by dressing like a minister, gathering crowds, and preaching his father’s sermons. In his mind, the joke was that they would listen to anyone, even an unbeliever.

He eventually gathered a crowd in Pennepack, outside Philadelphia, and began preaching one of his father’s sermons. The people listened intently. He was, by all accounts, a gifted preacher. Then, without warning, he stopped mid-sentence. Witnesses later said he looked “astonished,” as though he had been “seized with a sudden disorder.” Tears streamed down his face. At last, he confessed to the crowd, “I look like a minister, but I am a lost soul. I know nothing of the grace of God. I am an imposter.” He tore off his father’s ministerial garb and rushed to find the nearest Baptist minister, who turned out to be Thomas Dungan.

Dungan became convinced that Elias had been genuinely converted and baptized him. The church reasoned that since he clearly could preach, and now truly believed, he should continue. Elias did just that, going on to plant Baptist churches throughout the Middle Colonies.

His story calls to mind the apostle Paul’s words about those who preached Christ with impure motives: “[They] proclaim Christ out of selfish ambition, not sincerely … What then? Only that in every way, whether in pretense or in truth, Christ is proclaimed, and in that I rejoice” (Philippians 1:17–18). Paul may not have envisioned a man being converted through his own insincere preaching, but that is precisely what happened in the case of Elias Keach.

The Philadelphia Baptist Association and Confessional Identity

Among the churches planted by Elias Keach, five came together in 1707 to form the first Baptist association in America, known as the Philadelphia Baptist Association. Its formation was significant for several reasons.

First, it marked the first time Baptists in America were able to organize formally. Until then, most Baptist churches had existed in survival mode. Simply remaining intact and keeping their doors open was an accomplishment. The association provided a means for mutual help and support. Each church remained fully autonomous, but the association strengthened their collective witness by enabling them to assist one another more effectively.

Second, the association revealed a deep unity among Baptist churches, particularly in doctrine. The Philadelphia Baptists formally adopted the 1689 Second London Confession as their confession of faith. Though they initially represented only a small number of churches, this confession would soon shape Baptist theology throughout the colonies. It brought clarity and stability to Baptist belief, and even the relatively few Arminian or General Baptist congregations at the time would soon embrace the Calvinism articulated in the 1689 Confession.

Third, the formation of the Philadelphia Association gave Baptists a clear confessional identity. It declared to themselves and to the surrounding world that they knew what they believed. They were not an unorganized movement drifting from one idea to another. They possessed a defined theological foundation, expressed in their confession. That identity would prove crucial as Baptists entered a new phase of life and growth in America.

Revival, Division, and the Rise of the Separate Baptists

In the 1740s, America experienced the First Great Awakening. Revival swept through the colonies, with George Whitefield serving as its primary catalyst. A British evangelist, Whitefield could preach outdoors to thousands of people, without amplification, and hold them spellbound. His message was simple and direct: you must be born again. True Christianity, he argued, was not a matter of church attendance or civic membership. It required a personal, experiential encounter with God.

This revival split the Congregationalists sharply. The so-called Old Lights rejected the movement, viewing it as overly emotional and disorderly. The New Lights embraced it but soon faced a serious problem. If a person must be born again, what does that mean for those who entered the church as infants? In most towns, church membership effectively included everyone born there. The revival forced them to confront the reality that many church members may not have experienced a new birth. That logic led many toward Baptist convictions—namely, regenerate church membership and, inevitably, believer’s baptism.

Here, the story takes another ironic turn. These New Light Congregationalists, who had once opposed and persecuted Baptists, gave rise to a new Baptist movement known as the Separate Baptists. This movement was led by Shubal Stearns. It has been said that if Roger Williams was the intellectual and John Clarke the statesman, Stearns was the flamethrower. Contemporaries described him as having “piercing eyes” and a “musical voice.” He was a deeply charismatic preacher.

In 1755, Stearns and others felt compelled to leave New England and move south, settling in Sandy Creek, North Carolina.

The Separate Baptists differed markedly from the Particular Baptists, who would soon be known as Regular Baptists. Separate Baptist preaching was intense and urgent. Stearns himself was known for his passion and magnetism. One listener said that when Stearns fixed his eyes on him, he felt like a bird staring at a rattlesnake, unable to look away. The preaching lacked the systematic polish of the Regulars. It has been described as a “holy whining,” marked by a musical cadence. Congregations were often visibly moved. People cried out, collapsed, and responded loudly. The atmosphere was noisy and chaotic.

Yet it was highly effective. The Sandy Creek church grew from sixteen members to forty-two churches with 125 ministers. The Separate Baptist style spread rapidly, but it also brought conflict with the Regular Baptists. The Regulars were orderly, educated, and confessional. The Separates were emotional, expressive, and deeply suspicious of what they saw as the Regulars’ subdued, lifeless worship. The Regulars viewed the Separates as disorderly and potentially heretical. The Separates regarded the Regulars as cold, spiritually dead, and uncomfortably similar to the Congregationalism they had left behind.

Much of the tension centered on confessionalism. The Separates feared that a written confession would replace Scripture, responding with the claim, “We have no creed but the Bible.”

This division, however, did not last. By the end of the 18th century, the two groups began to understand one another and move toward unity. The Regulars came to recognize that the Separates, though lacking formal confessions, were thoroughly orthodox and even Calvinist, and remarkably effective in evangelism. The Separates, in turn, realized that emotion alone could not sustain the church. Stability and structure were necessary, and the Regulars provided both. By the 1780s, Baptist associations increasingly brought the two together, and nearly half of the Separate Baptists had become Regulars.

The result was a formidable movement. The fire of the Separates combined with the doctrinal clarity and stability of the Regulars produced a Baptist identity marked by both theological conservatism and evangelistic zeal. Baptists multiplied, their influence expanded, and that growth would soon intersect with the unfolding events of the American Revolution.

Baptists, the Revolution, and the Fight for Religious Liberty

When the colonies began defying the king of England, Baptists, especially in New England, found themselves in a complicated position. They had no love for the monarchy, but they were also wary of replacing one form of tyranny with another. Since the Act of Toleration in 1689, Baptists were generally free to worship in places like Massachusetts, yet they were still required to pay taxes to support the Congregationalist Church. Failure to pay could result in property seizure or imprisonment. As a result, Baptists found themselves both inside and outside the conflict with England.

A Baptist preacher and historian named Isaac Backus emerged as a leading voice in this moment. He turned the colonies’ chief complaint against England back on his fellow Americans. They protested “taxation without representation,” and Backus responded, “That’s exactly what you’re doing to the Baptists. Why is it unjust when it comes to tea, but not when it comes to religion?”

In keeping with the spirit of the age, Backus urged Baptists to practice civil disobedience. He encouraged them to stop paying taxes to support the state church. The consequences were swift. Baptist property was seized, and many were imprisoned. This took place throughout New England and in Virginia, where the Anglican Church held power. From jail cells, Baptist preachers continued their protest by preaching through the windows. Authorities responded by burning brimstone outside the cells and hiring drummers to drown them out. Instead of silencing the Baptists, these tactics drew greater attention to their cause and stirred widespread sympathy.

Two influential figures took notice: James Madison and Thomas Jefferson. Neither man was an orthodox Christian. Both were Enlightenment thinkers, committed to liberty and skilled in politics, with little personal interest in religion. Yet they recognized that the Revolution would fall short of its aims if Baptists lacked freedom. They also recognized that Baptists had become a significant voting bloc. Protecting Baptist liberty was both principled and politically wise.

One Baptist preacher, in particular, played a decisive role: John Leland. In Madison’s case, Leland effectively threatened to withdraw Baptist support during his congressional campaign unless Madison committed to pursuing a constitutional amendment guaranteeing religious liberty. Madison would later draft the First Amendment.

As for Jefferson, Leland’s influence was less direct. Still, Leland rallied Baptist support behind him. Their relationship was an unlikely one. They worked toward the same goal of religious freedom, while driven by very different motivations. Jefferson’s reasons were secular, but Leland supported him nonetheless. After Jefferson became president, he even invited Leland to preach before Congress.

And with that, after nearly two centuries of struggle, the Baptists finally secured religious freedom.

Final Reflections on the Baptist Struggle for Liberty

To conclude, I want to make two points.

First, it is important to recognize that the Baptists’ ultimate goal was never political. Political action became necessary to carry out the church’s mission, but the mission itself did not aim to create an ideal political system or government. These early Baptists simply wanted to worship God as he commands and to make disciples as he commands, “baptizing [believers] in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit” (Matthew 28:19).

From the beginning, they understood that in a parish system, where everyone was baptized as an infant, the practice of believer’s baptism and a regenerate church membership would require liberty of conscience. They took Peter’s words seriously: “We must obey God rather than men” (Acts 5:29). Obedience to God meant breaking unjust laws and enduring persecution. If it had not been illegal to obey God in this way, it is doubtful the Baptists would have ever felt compelled to become as involved in political matters as they did.

Second, I’ll offer an observation. While reading Baptist history, I began a book titled The History of Religious Liberty, which has underscored just how remarkable God’s providence has been throughout history. It has also made me deeply thankful. You and I, if you happen to be an American Baptist, are beneficiaries of immense suffering and turmoil. Blood has been shed, and tears have been poured out to secure the freedoms we now enjoy. My prayer is that we would never take those freedoms for granted.